Building a generic web crawler/spider in Python

I’ve been doing web crawling and web scraping for years. It’s funny but it was actually the interest in web crawling that introduced me to Python as a programming language and made me give up my precious PHP which was what I was coding with earlier in my career.

Python simply had much better tooling, and the language itself was more suitable for building background processes and applications that was not just websites depending on a HTTP request for execution (unlike PHP where everything revolve around building something that serves web requests).

My first web crawler was crawling a single massive website of product listings, and I was parsing prices, product names, addresses, contact information and more by hardcoding what table cell, what CSS class name, header and so on to read the data from.

This worked extremely well… for about a week. Pretty soon the source website did updates to their product pages and suddenly my parsing broke. I updated my parser and then two weeks later something else broke which required me to manually fix it. It was a never ending cat and mouse game where they were updating their website, and I was updating my crawler to match their changes…

I recently I launched a real estate portal called Homest which is not only crawling a single source, but hundreds of sources. This is done with a single generic crawler that can crawl any of these sites without having to have detailed knowledge of the actual HTML structure that is making up these sources.

How did I do this?

Architecture of my web crawler application

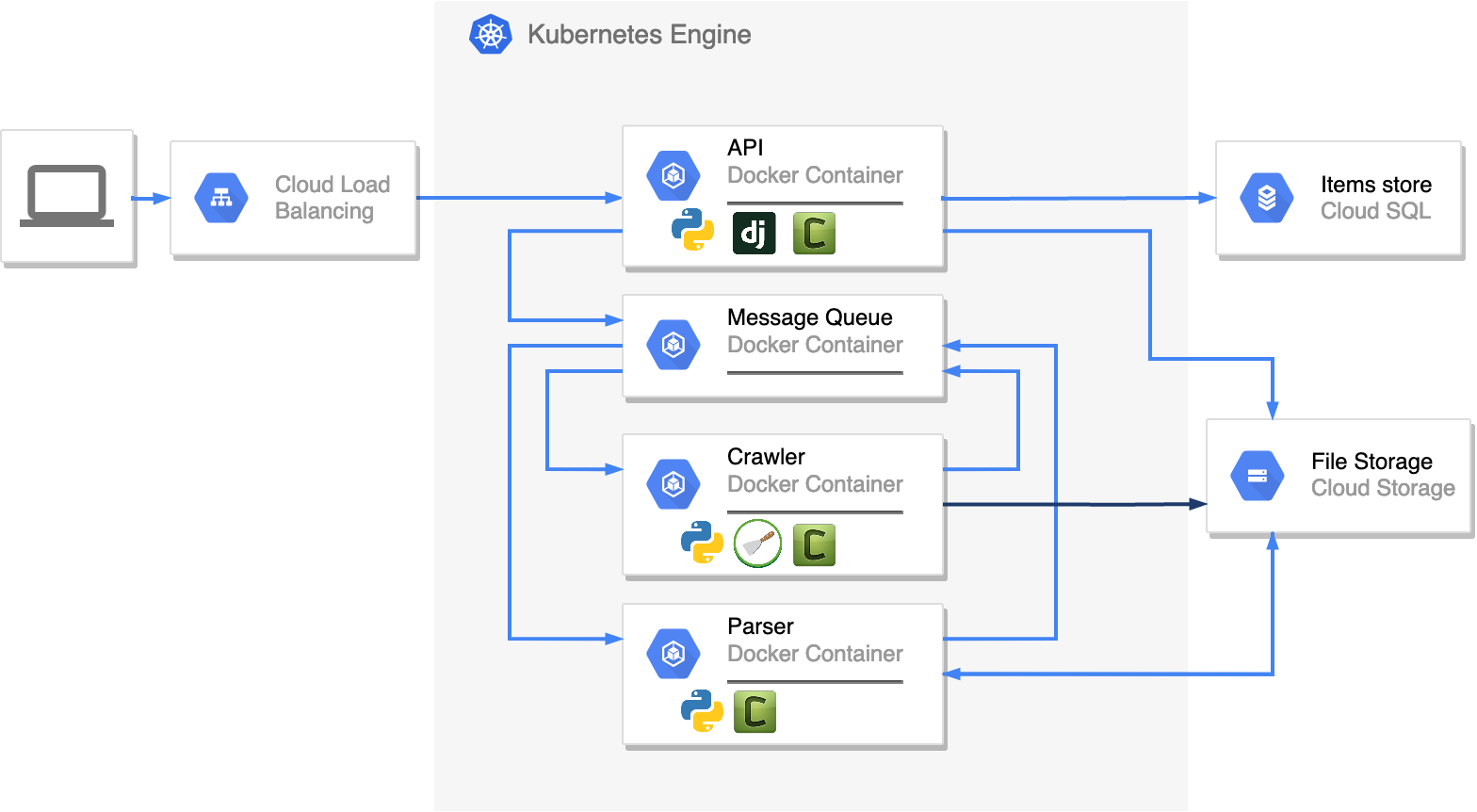

Lessons learned from previous crawling projects made me setup this project with a much better micro-service architecture from day 1. I’m not a person that push for micro-services for ever project, I agree that it can be overkill for plenty of applications, but in this use case I really think its the best way to go.

- We have a central API that stores data and orchestrates requests and processes.

- We have a “crawler” service that is only concerned about crawling websites and storing the HTML on disk. It does not do any parsing of content at all.

- We have a “parser” service that is responsible for parsing information from the HTML stored by the crawler.

- All services communicate with eachother asynchronously using Celery and Message Queues.

Building a web crawler with Scrapy

The crawler in this case use Scrapy together with Splash to be able to crawl websites and render any content loaded by javascript.

As mentioned in the architecture section above, the only concern for the crawler is to “crawl” websites. We are not concerned with parsing information from the HTML with this service. This allows us to focus on the following important pieces:

- Performance and crawling large amounts of data in efficient manners.

- Render Javascript and content loaded by client.

- Avoiding anti-crawler mechanisms that certain websites implement.

- Defining rules such as what links that should be followed/crawled, what robots.txt that should be respected, if we should rely on the XML sitemap or not etc.

These issues listed above is more than enough scope for a single application and it is a never ending list of work and iteration that can be applied to perfect it further.

What the crawler does is downloading the HTML of the real estate listings and asynchronously send it back to our API with some meta data about the page (urls, date crawled etc) where it get stored and awaiting to be parsed.

There is some massive benefit to separating the “crawler” from the “parser” in this way:

- Parsing is often an iterative process. By crawling and storing the HTML once, and then parsing it separately, we avoid having to re-crawl and re-download the same HTML content over and over again as we iterate.

- We can re-parse very old content as our parser improves. For example, we might have HTML from 6 months ago that we want to re-parse with our updated parser that now parse some additinal data or information from the page. If we did not store the HTML the page might already be gone from the internet at this time. This is especially true for product and listing pages that might only exists for a few weeks.

- We can scale each process independantly. For example, our crawler might be able to crawl pages 10x faster than our parser can parse them. This means that we can easily create 10x parser workers compared to crawler workers and use our resources more efficiently.

Building a generic HTML parser

The secret sauce in building a project like this that can scale, be stable and work reliably over long periods of time is in the parser. It is key to build a parser that can work across “any” website and not make hyper-custom parsers that only work for certain sources or certain pages. If it is tailored to each source it makes it impossible to scale, and it makes it very fragile.

So how do I parse data from HTML pages without relying on HTML elements, classes and table cells?

There are a few challenges to this:

- Many real estate listing pages contain multiple listings. It might contain “the main listing” and then also list multiple “recommended” or “similar” listings at the bottom of the page or in the sidebar. Which one of these datasets are the listing we are interested in?

- Wide variaty in wording/terminology/language between different sources. For example some might call things “3 beds” and other might call it “3 bedrooms”.

- Images and files. Which files are photos of the listing, floorplans, portraits of the real estate agents, advertisements etc?

All of these challanges can be solved by relying less on HTML, and instead rely on Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning.

For example:

- We can train a machine learning model to identify which part of a website that is “the main content” and what is the “extra content” such as navigation, footers and less important information. This helps us understand what address, price and house features that is part of our “main listing” and what features that are part of “extra listings” on the page.

- We can use many NLP techniques to simplify the texts, remove words that are less interesting (such as stopwords), remove grammar and identify language to make it much easier to parse the actual text. See more on Python’s NLTK package.

- We can build neural networks that use image recognition techniques to tag images as “real estate photos”, “portraits”, “exteriors photos”, “floorplans” etc to make it easier to parse the correct images and files.

Communicating Asynchronously using Celery

As you can see on the architecture diagram above, each “functionality” that make up our application is its own micro-service running as its own Docker container, with its own codebase etc. Since there is quite a lot of processing times and IO times for the different tasks, I believe that an asynchronous communication model makes a lot of sense compared to a synchronous HTTP API request approach.

What this means in practice is that we use message queues to “queue up tasks”, and then we use Celery workers to process these tasks one by one in the pace that the available resources allow for.

For example, each crawled page generates a equivelant “parsing task” for that HTML, but it might take 1 seconds to crawl a page but 5 seconds to parse it. So the queue for “parsing tasks” might build up much faster than the queue for “crawling tasks”. This means that we can easily scale each worker independantly to match the need. We might for example need 5 parser workers for each crawler worker to ensure that we can parse the pages that the crawler crawls in a reasonable amount of time.